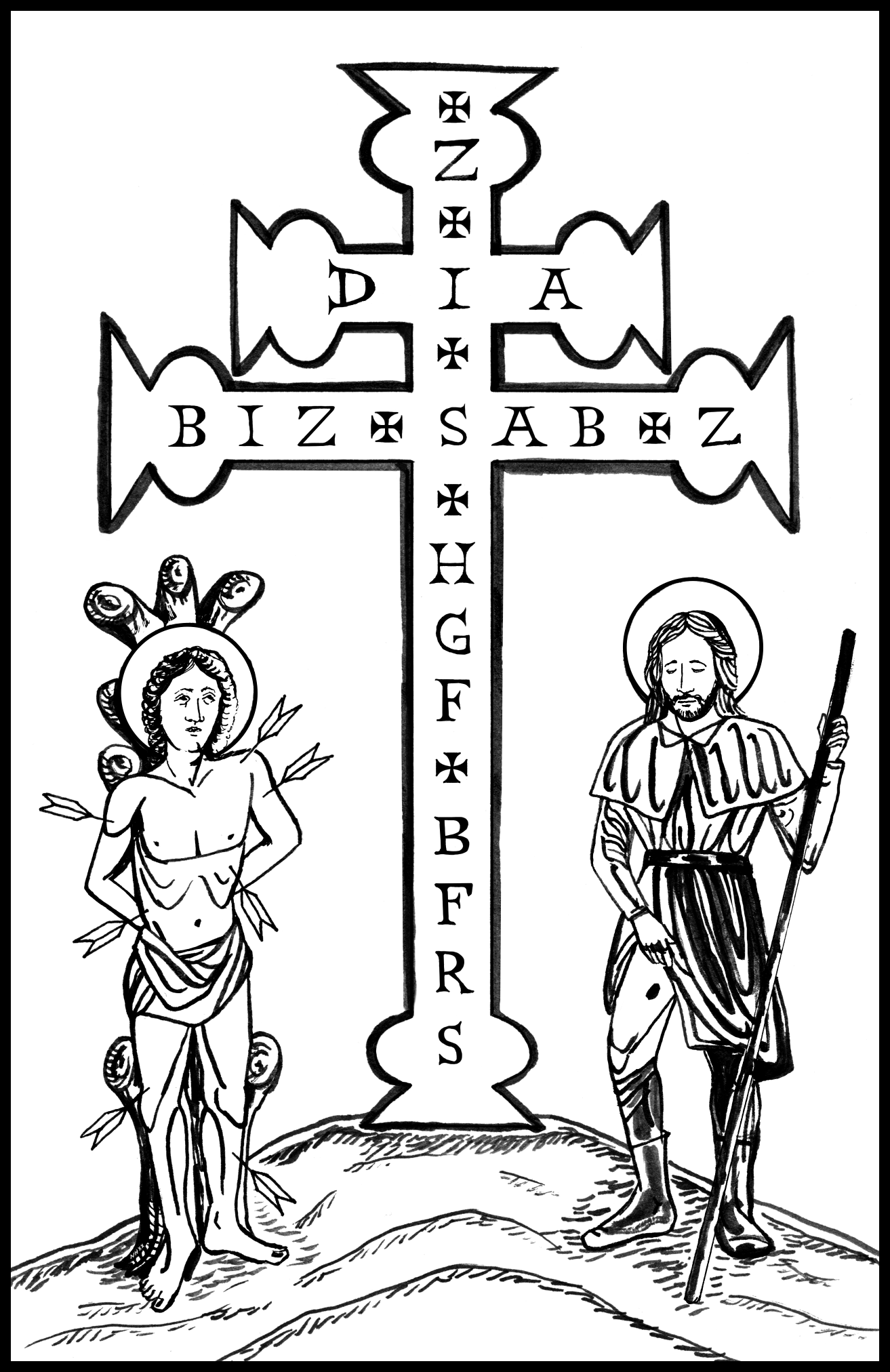

Prayer to St Sebastian from 1349

O St Sebastian, guard and defend me, morning and evening, every minute of every hour, while I am still of sound mind; and, Martyr, diminish the strength of that vile illness called an epidemic which is threatening me. Protect and keep me and all my friends from this plague. We put our trust in God and St Mary, and in you, O Holy Martyr. You, citizen of Milan, could, through God’s power, halt this pestilence if you chose. O Martyr Sebastian! Be with us always, and by your merits keep us safe and sound and protected from plague. Commend us to the Trinity and to the Virgin Mary, so that when we die we may have our reward: to behold God in the company of martyrs.

It’s been a strange year for me and Saint Sebastian.

The first significant encounter I had with Saint Sebastian (the saint shot through with arrows) was within the pages of Yukio Mishima’s coming-of-age story Confessions of a Mask. I had picked it up as a young teenager knowing it was a notorious work. In it the main character Kochan’s nascent queer sexuality is sparked pursuing Renaissance art books in his father’s study. What becomes the focus of his desire is in the exotic representations of Saint Sebastian who’s youthful body is naked, twisted and injured.

It is true, representations of the saint have an intimacy, a tenderness that is seductive and suggestive. It’s as though the homoerotic gaze is essential to the iconography. Mishima writes luridly and extensively about the eroticism of this image. And like the way that Sebastian’s martyrdom is a mirror for Christ’s, Kochan’s gaze was a mirror for my own.

And so Sebastian traveled with me as part of a secret code of gay male sexuality—a hidden note passed by dead painters. I looked for Mishima’s book “Ba Ra Kei” where photographs of author mimic the saint. I peered at tiny scans on websites. Later in high school, I started a wry electropop band with my friends called “Saint Sebastian”. The name felt to me like a nod to my Catholic school upbringing, my delight in hagiographies and as something coded.

But the what escaped me about the saint was Sebastian’s connection to disease. I think in times between plagues we forget what plague-time is like, even generation to generation. There are leftovers, yes, there’s Diamanda Galas performing Plague Mass, there’s art—there’s so much art from the AIDS Crisis—and then so much forgetting and so much absence, so much space for us to forget.

So idly I wonder if in the absence of plague, does the erotic aspect of this saint dominate? I remember seeing Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane (made in 1976) once when I was in college. I can recall how beautiful it was. It was Jarman’s first film, and I feel tempted knowing that Sebastian is a plague saint to connect it to the AIDS crisis even if this feels a bit perverse. In 1994 Jarman’s last movie was Blue documented the director’s experience of dying from AIDS. The entire film the color blue, which was at the time the only color he could see. Jarman was always something of a prophet, so I want to intertwine the two, connect Sebastian’s erotic suffering to the other, and yet…

But in the ellipsis between AZT and the 2020 PANDEMIC (writ large across the world) Sebastian settles back to being the patron saint of athletes as evidenced by medallions I found being sold online by catholicompany. He settles back to being the unofficial patron saint of the gay community: in poorly executed fashion editorials for gay magazines. My life mostly fits into this ellipsis, and my relationship to the saint is peripheral. But he pops up: I spend a lot of time thinking about a sculpture of him I see in Little Italy and my former roommate moves near a cathedral with his relic in Majorca and uses it as a reason to come visit (I don’t visit).

Plague-time

It’s April 2020 and I’m in New York City finding myself praying the rosary, drawing pictures of Saint Sebastian and setting up little altars to him an other plague saints. His role as intercessor against the plague suddenly has become dominant. The iconography is the same, of course, but my eye is drawn to his face which is turned up to heaven.

And here is the strangeness of image, the slipperiness of an icon. Rather than a shift in focus there is a shift in identification. Instead of gazing at him now I identify with the saint as he is being tortured, stripped of agency, thinking “will this next arrow be the one?” The saint’s character has shifted as well: instead of a mere object of adoration he is a soldier who endures torment and bestows perseverance through plague-time.

And what does an epidemic do other than bind and torture? If it’s not simply an effect of the disease it’s an effect of the state methods to curb the outbreak. But in any case, it’s becomes a situation so complex with so many actors (invisible and visible) it is solidly beyond individual’s grasp. It’s a humbling experience, one that is forgotten during un-plague-time’s amnesia. Saint Sebastian can cut through these layers of history connecting to deeper older memories. The voices praying for intercession become synchronized.

It seems to me that the weirdness of saints can be demonstrated in Sebastian. It’s in his complex cultural ambience, his ability to go from thin costume to intercessor. Saints grow and change in popularity picking up patronages, spheres and communities. They wane in popularity and become forgotten. But when remembered they form a direct channel to a complex past and a complex history, one that is more focused on human fears and concerns, love and care, than holy transcendence.